Snapshots with Stories

38 – Thinking of Ataka

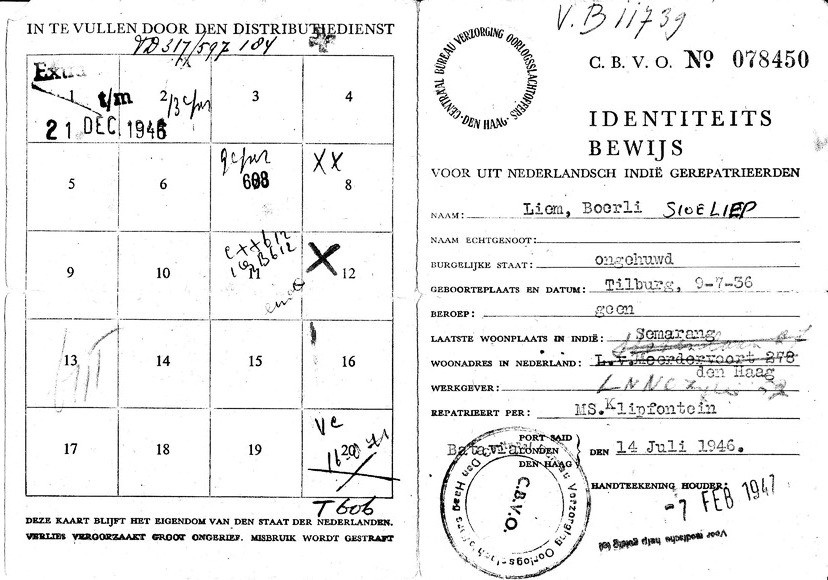

Photo 1: S.L. Liem’s identity card

Thinking of Ataka, I see an endless sandy desert rolling from the Gulf of Suez to the west, forming a mound somewhere on the horizon. Ataka was a welcome break during the exhausting oversseas voyage many repatriates experienced fleeing the desolate Dutch Indies between 1945 and 1947. A journey to an unfamiliar destination: it began for many with anxiety and questions of what would lay ahead.

Attempting to locate Ataka on a map, is likely to end in futilty. We know there is a mountain named Jebel Ataka, and Ataka should be located somewhere at its base. But Ataka only exists in the memory of sea voyagers of days gone by. In my memory it was a large camp, but perhaps it was only a big shelter. In any case, to a 10-year old boy disembarking after a long journey, it was something big and it was quite exciting. Crossing the desert in a train was quite an adventure. Cheerful people, men and women, some in uniform, welcomed us at the end of the journey. For many years following the Japanese invasion of Java in 1942 I could not have imagined a reception by smiling people in uniform.

I noticed the music immediately on approaching the shelters decorated with flags. A small orchestra played popular music from the 1930s and 1940s. The catchy tunes excited some people to dance in that shelter in the desert. It was dance music from the pre-war period, according to the adults among us. Now it is referred to as ‘Swing’. Indeed, 70 years later this lively, nostalgic music still cheers me up.

You could get almost anything in that shelter. There was plenty of food and drink. We had to line up past tables and cubicles where we were given goods. We tried on clothes, then put them in a duffle bag and took them with us. It struck me that the range of clothes offered was mainly green. There was a merry atmosphere in that shelter, reminiscent of a ‘Pasar Malam’. The difference was the sound, smell and wares. As many others I was X-rayed. In the Red Cross’ booth, chest X-rays were made in the detection of tuberculosis, as many people were underfed during the war and therefore prone to that disease. Fortunately, I did not have tuberculosis.

By today’s standards we know that the port, where our ship the M.S. Klipfontein moored at the entrance of Suez canal, was the port of Adabiya, an artificial port built in World War II by the Allies for supplies during the war in the desert against the German army, which was led by General Rommel. The train must have gone inland for about 10 km and stopped at an encampment set up by the Allies during the war and now used to accommodate repatriates and supply them with clothing and footwear for the new fatherland. Many people had lost everything and had very little luggage when they embarked the ship at Tandjong Priok.

At first, all the warm clothing in the desert seemed unnecessary weight to me, as we were accustomed to walking around all day barefoot, wearing only shorts and shirts. I had to think about that often, when walking from the guesthouse on the Laan van Nieuw Oost-Indië (Avenue of New East-Indies), along the Haagse Bosch to the bridging school on the Weissenbruchstreet, wearing an oversized coat and feeling frozen. In hindsight we were happy to have them, as in my memory the winter of 1946-47 was harsh and icy, with frozen ditches and puddles.

Photo 2: S.L. Liem’s clothing list

Upon departure from Batavia on 14 July 1946, our family was given a special identity card by the C.B.V.O., Centraal Bureau Verzorging Oorlogsslachtoffers (Central agency for the Care of War Victims). The card listed all the goods we received from the C.B.V.O. until February 1947. “‘Fully dressed”, it said on my card after the Ataka visit. This was booked as a ƒ50 advance, to be repaid at a later date. My 2-year old sister was also fully dressed. Furthermore, 6 allowances had been noted between July ’46 and February ’47, totalling an amount of ƒ100 for the adults and ƒ65 for the minors. On my parents’ passes an amount of ƒ50 was noted for the acquisition of Ataka-clothing. A salient detail in this regard is the recovery of these advancements. Many relief goods were donated by the United States, collected by the Red Cross, but also specially purchased by the Dutch government from surplus stocks of army goods. The Ataka camp was in use until January 1947. Later, clothing was handed out on board at Port Said, or during the journey through the Suez Canal. I don’t know what happened to Ataka. Perhaps it reverted to a mound of sand in the desert once again.

Boelli S.L.Liem, June 2016

Sources (Literature and facts on Ataka are scarce) :

- “Koers West”, a commemorative booklet of the Repatriëringsdienst Indië, published by Boom-Ruygrok in Haarlem. In the chapter “De grote verkleedpartij” of his book “Het Oostindisch Kampsyndroom” Rudy Kousbroek describes the dispensing of clothing in Ataka.

- Information on Ataka can be found on a few websites on internet. Absolutely worth viewing is the photo collection of Willem van de Poll – Repatrianten1946 (Google search).

- Stories and photos on this episode of the Indies history can be also be found on the website of Java Post (www.javapost.nl)